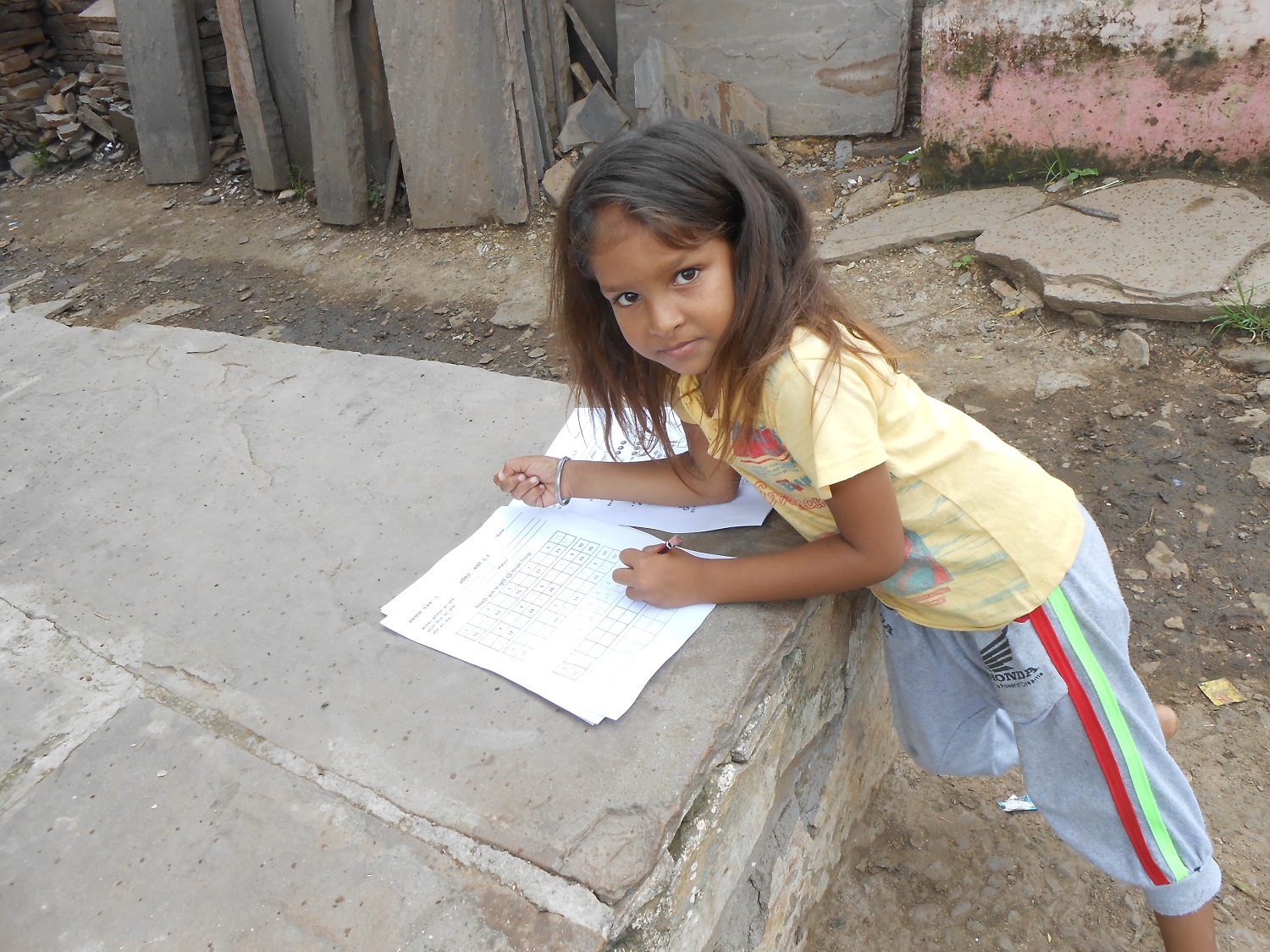

No Child Left Behind: helping to expand the life opportunities of adolescent girls.

A major focus of the work being performed by Manjari* within the community of Budhpura is in improving the health and prospects of adolescent girls.

Twenty-seven sessions have been delivered to adolescent groups in the last few months, covering topics such as literacy and entrepreneurship. One of the biggest benefits of this programme is in expanding the horizons of young women, helping them to see that their future is not “set in stone”.

Around 250 girls are involved in the programme; less than a third them are still in school, and some do occasional work in the stone yards. Some are, indeed, married. The legal age of marriage in India is 18.

Just as we explained in previous articles that child labour is a result of a complex situation, so is under-age marriage. It’s a concern that India as a whole has been trying to address for decades. The situation is improving and numbers are falling. In Rajasthan, however, the percentage of under-age marriages is much higher than the national average; Manish Singh, Secretary of Manjari reports that, in the Budhpura area, around 32% of marriages are under age.

The negative consequences of child marriage are many. Girls who marry very young have fewer educational opportunities, which affects their economic status and has a consequent impact on the economy of the country. Teenage pregnancy increases population growth because of the extra years of fertility. Young brides are more likely to be the victim of domestic violence and, according to the International Women’s Health Coalition, girls under the age of 15 are nearly five times more likely to die during childbirth, compared with women in their 20s; they are also at more risk of injuries resulting from pregnancy and childbirth.

The health of the children they bear can also suffer; often babies are underweight, and there’s a risk of their growing up stunted. All of this contributes to a cycle of poverty, so there is enormous benefit to eradicating under-age marriage.

However tempting it is to condemn a situation, no problem has a single cause, and no problem has a single solution.

The work of Manjari and other agencies involved has to take into account multiple intertwining strands. “It’s how society perceives women,” explains Manish. “Are they considered a burden and responsibility, or are they people full of human potential?”

Poverty also plays a big role. “In India marriages are big business, so when an older girl is being married, a young girl is also married with her just to save money.”

One of the ways to combat early marriage is education. Women with twelve or more years at school are far more likely to get married in their twenties than those with no schooling.

It is, however, no coincidence that girls tend to drop out of school when they reach puberty. Menstruation is a major issue. and menstrual hygiene is another of the subjects covered in the sessions attended by the girls.

Some of the problems surrounding periods are cultural; when she’s menstruating, a girl can find herself subject to restrictions on behaviour and movement passed on by parents and siblings. Unsafe menstrual practices, such as reusing old cloths, are not uncommon in rural areas; they increase the danger of contracting reproductive tract infections, which can severely impact fertility later on.

The pandemic has in no way helped. There’s been a huge shortage of sanitary pads, with seven out of ten girls finding difficulty in obtaining them during lockdown, according to a study by the NGO Population Foundation of India last August. Interestingly, Poonam Muttreja, its executive director, was reported in the Hindustan Times as saying: “It takes tremendous convincing on the part of frontline workers to encourage and educate school-going girls to use sanitary napkins.”

Perhaps this has something to do with the financial aspect. Girls have been reluctant in the past to buy sanitary towels because of their high cost, but they’ve also been embarrassed to them in male-run shops.

This makes the sessions incredibly important in educating young women in menstrual health, but without access to sanitary towels, the education is in vain. Varun Sharma, Programmes Director of Aravali, one of the agencies involved in supporting the work of Manjari, said, “There is a very big issue of women not being able to access sanitary napkins. In the absence of that, their entire life suffers.”

A lack of sanitary towels leads to girls dropping out of school—one of the very things which can help their life chances. As part of the solution, Manish has got together four entrepreneurs, to procure good-quality low-price sanitary napkins. They have now started selling these to women.

It’s one small building block in giving adolescent girls life options which in the past weren’t even dreamed of. The self-help groups that are empowering women financially is another. There are other building blocks too. All are combining to create a structure that gives women a more recognized value in their community.

*For more information on Manjari, see The NGO helping to eradicate child labour.